The fact of the matter is much of country music – both classic and contemporary – would not exist as we now know it were it not for Maybelle Carter and her work with the first family of country music, the Carter Family. An unprepossessingly talented guitarist with a keen ear for good songs, Mother Maybelle is arguably the wellspring from which all subsequent country artists have sprung. Her approach to the form, nuanced guitar work and the tight familial harmonies all played a substantial role in shaping what would become Country & Western and finally just country music.

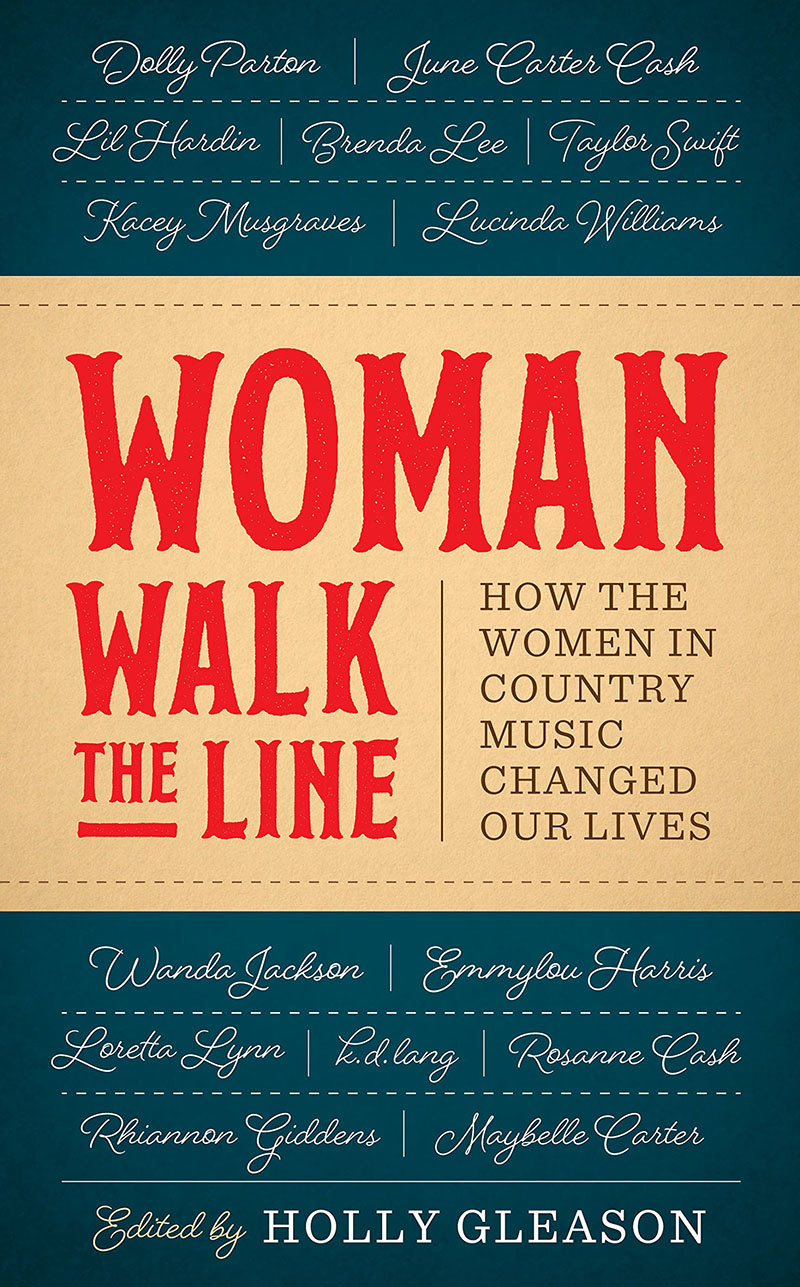

Woman Walk the Line: How the Women in Country Music Changed Our Lives

Holly Gleason

September 2017

In Woman Walk the Line: How the Women in Country Music Changed Our Lives, more than two dozen artists and writers pay homage to their predecessors, expounding often at length on how each of the marque artists covered within the collection shaped their lives, perceptions of country music and, in many cases, their careers as both professional women and female musicians. From the more abstract, autobiographical and tangentially-related to the deeply personal, the essays collected herein run the gamut. Eulogizing her late step-mother, Rosanne Cash – who herself is one of the titular women in addition to being a contributor – offers a touching, heartfelt series of recollections detailing the person that was June Carter Cash rather than the musician and public figure. It offers a lovingly humanizing portrait of these often-larger-than-life giants in the field of modern music, providing a look behind the curtain at the person behind the persona.

Running roughly chronological, Woman Walk the Line moves from Maybelle Carter and Wanda Jackson up through Kacey Musgraves and Rhiannon Giddens and nearly all points in between, covering the whole of country music’s increasingly broad spectrum of artists, styles, and decidedly unique characters. In what other genre can you find septa- and octogenarians still strutting their stuff like those a third their age (Dolly Parton and Loretta Lynn, respectively)? Indeed, where female pop musicians tend to age out of the field, country musicians tend to possess a greater reverence for their predecessors, lionizing their greatness and proclaiming their influence at each and every opportunity.

While all the expected artists are present and accounted for (Parton, Carter Cash, Lynn, Emmylou Harris, et. al.), it’s the comparatively lesser-known artists whose entries tend to prove the most fascinating. The collection’s second essay, Alice Randall’s “That’s How I Got to Memphis” offers a unique look at an otherwise unlikely entry within the field of country music: Lil Hardin. The wife of Louis Armstrong, Hardin initially seems an odd choice. Better known for her blues and contributions to jazz, Randall is quick to point out that, like Maybelle Carter, Lil Hardin was present and accounted for at the beginning of country music, accompanying Jimmie Rodgers legendary “Blue Yodel #9.” This is not only revolutionary for the fact that Hardin was a woman, but that she was a black woman at a time of rampant racism in the south playing on one of the defining early tracks of a style of music almost exclusively the purview of white performers.

Randall uses this to show the impact of African Americans on the shaping of country music from the start, not only in the stylistic and thematic similarities between country and the blues, but also the geographic and cultural similarities from which each sprang, largely in tandem during the pre-war years and early days of sound recording. Hardin’s immutable contribution to country music shows the literal influence of African American musical idioms rather than taking the usual route wherein the influence is generally more theoretical in nature, an abstraction attributed to the sharing of a specific time and space.

At its heart, Woman Walk the Line functions as a love letter from one generation to the next, a series of sincere thank-yous and explorations of lives lived in a manner often vastly different from any that came before. Yet in their very being, they have opened countless doors and opportunities for those who’ve come along afterward, following in their ideological footsteps and taking full advantage of the opportunities they are afforded while remaining cognizant of those challenges and hurdles that still remain and their respective roles in overcoming each for future generations of women. In this, Woman Walk the Line is only outwardly concerned with country music, using some of its biggest trailblazers to explore the broader issue of women’s perception in a largely male-dominated world in general.

Given the current social and political climate wherein it seems nearly everyone you’ve ever heard of has behaved as an egregious sexual predator, these types of female-centric explorations are even more important, showing a solidarity that transcends mere genre, racial, or social status. Perhaps thematically a bit high-minded for the traditional ideal of country music and its practitioners, Woman Walk the Line nonetheless serves a vital role in the shaping of the history of country music equally at the hands of both men and women. If only such equal footing could not only be recognized, but implemented in our daily lives. Perhaps taking a page from country music’s reverence for its founding mothers and fearless female trailblazers is as good a start as any in moving in the right direction. Only time will tell.

Related Articles Around the Web

This Article Was Originally Posted at www.einnews.com

http://www.einnews.com/article/421282271/zgwL14Yqg1m2CEcr?ref=rss&ecode=N1bP1tH84JZ33sYs