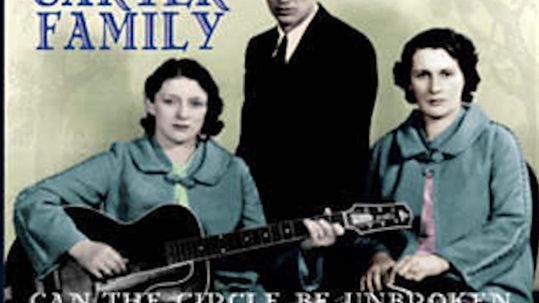

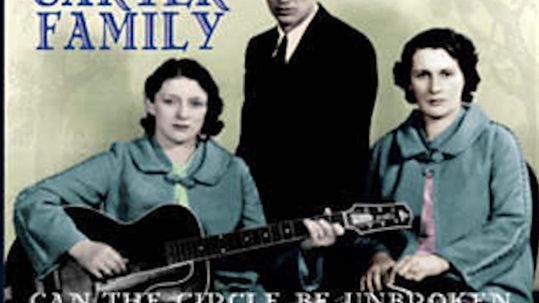

Mother Maybelle Carter was country music’s first guitar hero. Larry McCormack / The Tennessean / Juli Thanki

I was already grown and playing the autoharp when I first learned about the Carter Family. This was a surprisingly late development given that I have the same name as the family’s famous autoharpist, and that I, too, am a Virginian, but I finally learned their songs from a copy of Harry Smith’s “Anthology of American Folk Music” that I checked out of a Virginia public library. In old-time circles, it’s embarrassing to say you learned a tune from a recording rather than a person, but “Woman Walk the Line: How the Women in Country Music Changed Our Lives,” a new essay collection edited by Nashville-based writer Holly Gleason, has cured me of that embarrassment.

The musicians, music journalists and players whose essays make up this collection make no bones about the hours they have spent poring over the records of some of country’s most famous females — Dolly Parton, Loretta Lynn, Tanya Tucker and newer stars like Taylor Swift and Kacey Musgraves. Many of the writers had life-changing conversations backstage with an artist herself, while others cite the lyrics, licks and even political activism that made these first women of country music so unforgettable.

Yes, this book includes some of the biggest names in country music. But the essay collection is unique in centering on American roots heavy hitters like Hazel Dickens, Lil Hardin and Maybelle Carter — people who typically get less page time in considerations of country music. Not only will readers find some of the finest music writing in the business here, but they’ll also learn how the musicians’ evolution influenced each essayist’s own creative process. The result? Incredibly empowering writing about what it means to be an artist and a human being.

The book’s opening essay, “The Root of It All” by Caryn Rose, begins, “I found American folk music through what seemed like an unlikely back door: discovering Woody Guthrie via Pete Seeger via Bob Dylan while I was at Girl Scout camp.” Rose goes on to detail her surprise at discovering that many 1960s folk songs had a much earlier life. When she stumbled across a picture of Maybelle Carter in a music history book, she was intrigued by Carter’s way of “holding a guitar with absolute comfort, looking impassive —this was not a big deal to her.”

Early in her career as a music writer, Rose faced inane comments like, “You sure know a lot about music, for a girl.” Carter’s persistence in a male-dominated industry was a source of inspiration: “Maybelle Carter wasn’t hesitant or asking permission to be there, she was there; she wasn’t backing up some dude, she was the musician,” Rose writes. “She was a lead guitarist. She wasn’t decorative. She wasn’t optional. She was the main musician, and she acted like it.” At every stage of her memorable career, Mother Maybelle cut through the industry dross to play what she loved. Rose writes, “The phenomenal amount of just plain life she had to get through just to be able to do her job is more than most of us face in a lifetime. It’s a good thing to remember when you think things are getting hard.”

In “That’s How I Got to Memphis,” Alice Randall — Nashville songwriter, novelist and food writer — considers Lil Hardin, a jazz artist known for playing piano and for her partnership with Louis Armstrong (personally and professionally). Hardin was the original pianist on the Jimmie Rodgers tune “Blue Yodel #9.”

“What this means to me is that we, black women, have been present in country since almost the very beginning, at least since 1931,” Randall writes. “It’s a small circle.” Hardin’s life in music wasn’t easy, but she unflaggingly found a way to continue playing: “Raised in Memphis by a grandmother who had been a slave in Mississippi, Lil Hardin effectively constructed a life of creative liberation, inspiring others to follow after her —not in her footsteps, but in her spirit.” This spirit prepared Randall for the uphill climb she faced in Nashville in the early 1980s.

Ronni Lundy’s “The Plangent Bone” explains the force that is Hazel Dickens: “It’s as if all us hillbilly children got an extra sinew, a plangent bone, a tuning fork to recognize the ancient tones.” Though many performers can make this bone resonate, writes Lundy, Dickens “shapes and sends those notes from that very spot in her chest straight to the one in yours, bone to bone, soul to soul.” Dickens was one of 10 siblings who “grew up poor, dependent on a fickle coal economy whose boom-and-bust cycles had played havoc with the land and people for generations,” and she openly sang about the mistreatment and murder of miners at the hands of big coal companies: “Hers has become the voice of countless miners’ wives and children, crying out from the graveyards. Hers the plangent voice from deep within the mountain that contains their bones and souls.”

“When the sound, a voice, reaches directly to your core, your gut, your heart, your dreams — especially the dreams you didn’t even know you had — that’s when music matters,” writes Gleason.

“Woman Walk the Line” will touch readers to their cores — reminding them of their first musical loves and the difference between a musician and a star.

For more local book coverage, please visit http://chapter16.org, an online publication of Humanities Tennessee.

This Article Was Originally Posted at www.einnews.com

http://www.einnews.com/article/409547910/1VeTC7LgyHkZm4-1?ref=rss&ecode=N1bP1tH84JZ33sYs